Artwork: Satan Arousing the Fallen Angels, John Martin, 1824

A sermon delivered at Hebron United Presbyterian Church 10/8/23

Scriptures: Exodus 20:1–20; Matthew 4:1–11

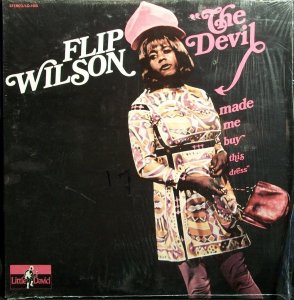

When I was young, my mom had a record collection that included a couple of Flip Wilson’s comedy albums. Flip Wilson was a comedian popular in the 60s and 70s. For a period of time in my teenage years, I listened to those albums constantly. This was before the internet, before cable or satellite TV made it to the boondocks where I lived, so this was my entertainment. Listening to Mom’s Flip Wilson records over and over again.

Flip Wilson had one particular series of sketches I found absolutely hilarious. These sketches featured him telling stories about Geraldine, who he sometimes imagined as a preacher’s wife, who had a penchant for spending her husband’s money on things she didn’t need and blaming it on the devil—the devil made me do it, she would say. In his TV comedy skits, he dressed the part of Geraldine, which of course didn’t come through on the albums, but the voice he did for Geraldine was funny enough.

The sketches were hilarious because Geraldine would concoct elaborate stories for how the devil made her do things of which her husband disapproved. The devil made her buy that expensive dress, she protested. The devil made her go into the store and try it on. The devil told her how good she looked in that dress. She would put up a fight—“devil, no,” she would say—but ultimately, the devil made her sign her husband’s name to a check. The devil made her buy that dress.

Flip Wilson’s play on Geraldine blaming the devil for her transgressions made for a pretty funny comedy album, but truth be told, there are lots of Christians who believe there really is a devil running around the world, invisibly tempting us to do things we should not do. It’s a prevalent belief in Christian circles. It is rooted in biblical passages like our Gospel reading this morning (Matthew 4:1–11), where the devil—Satan, or the tempter, as he is also called—appears as a supernatural character intent on sowing sin in people’s hearts and evil in the world.

But I’ll be honest with you: I don’t believe in the devil. I don’t believe that he exists; I don’t believe there is such a creature. The reason I don’t believe there is a devil is not primarily because it seems too fantastical, a mythical idea from another time. My main reason for not believing in the devil is that the idea of a devil is incompatible with Christian convictions I believe are true and important.

In the Bible, the character of Satan evolves over time. In the Old Testament book of Job, when Satan suggests to God that he test Job’s faithfulness by putting him through personal struggles and challenges, Satan isn’t God’s evil twin. He’s an angel, whose job apparently is to be God’s “devil’s advocate.”

By the time we get to the Gospel of Matthew and Jesus’ temptation in the desert, Satan looks more like a competitor with God, trying to get people (including Jesus) to follow his mischievous ways instead of God’s ways. Then, on our way out of the Bible in the Book of Revelation, Satan appears as God’s great enemy with whom Christ has to do cosmic battle at the end of history to establish the Kingdom of God on Earth. The devil in the Bible clearly gets promoted as we go along.

In the time since the texts in the Bible were written, Christians have given Satan even more of a backstory, none more influential than John Milton’s Paradise Lost, where Satan is depicted somewhat sympathetically as a fallen angel whose ambition got the best of him—pride indeed comes before the fall. And that has set the devil firmly in the Christian imagination as an angelic rival of God for our allegiance, someone with whom God is in a wrestling match over the moral fate of humankind.

The problem is, that depiction of Satan risks setting Satan up as God’s equal. It tempts us to imagine a moral universe in which there are two gods, the good God and an evil god, playing a high-stakes chess match with human beings, the outcome of which is yet to be determined. But this doesn’t fit with Christianity’s historic confession that there is one God, the God of the Bible, the God of goodness and power, one God who does all and knows all and assures all. In fact, early in its history, the church explicitly rejected dualism, the belief that there were competing gods vying for control over the world. God has no evil coequal. God alone rules the cosmos in God’s sovereign goodness.

Sin isn’t some little devil sitting on my shoulder. Sin is separation from God.

So my main problem with belief in the devil as it has been passed down through Christian tradition is theological: it offends my belief in one graciously powerful God, one supernatural force for goodness in the world. But I do have other problems with the devil. I think belief in the devil excessively spiritualizes badness, leading us to think badness exists in the world on a supernatural plane that humans can do nothing about, so the only thing we can do is tuck our heads between our knees and wait for the great battle of Armageddon between God and Satan at the end of time. A focus on the devil outsources badness, giving us someone else to blame it on rather than owning up to the reality that the bad in the world is the product of human attitudes, actions, and inactions. And history shows that a preoccupation with Satan, looking for his legions everywhere, makes it too easy to demonize other people. Whatever group we fear the most becomes in our eyes the devil’s agents, sowing chaos and evil. Christians have done that with Jews and Muslims and atheists, Protestants have done that with Catholics and Catholics have returned the favor, prominent American church leaders have done that with gay and trans people—even members of the opposite political party are accused of plotting with the devil these days!

So there’s a big theological and ethical downside to fixating on the devil as a supernatural force sowing evil in the world. That’s why I don’t believe in him. I think “Satan” was a way of talking about evil in the ancient world, a mythical construct to explain the very real death and destruction that was part of everyday life at that time.

Death and destruction and badness are, of course, a part of our every day, too. So if we don’t attribute it to a devil, where does it come from?

In a word, us. We are the devils that plague the moral universe. We are the devils that dare tussle with the goodness of God. We are the source of the badness we see in the world. At its most fundamental level, sin and evil happen in the world when we fail to trust God, when we separate ourselves from God in search of something else to make us feel safe and whole.

Sin as the failure to trust God is all over our readings today. Christians often think that faith means believing certain “facts” about God—I have faith because I assent to all of the things in the Apostles’ Creed. But historically, when the Bible talks about faith, when Martin Luther and John Calvin talk about faith, they don’t mean confession of certain doctrinal facts. They mean trusting in the power and goodness of God. To have faith is to trust that nothing in life or in death can separate us from the love of God (Romans 8). And sin is failing to have that trust. Sin is abandoning God’s will to go it alone, chart our own path, try to secure our own future, because we don’t think God has us.

We are the devils that plague the moral universe.

That’s the heart of those admonitions we call the Ten Commandments. God isn’t demanding arbitrary loyalty; God is saying, “Trust me!” Trust me, because I am the one who brought you out of slavery. I am the one who is going to get you through this wilderness into the Promised Land. Don’t go looking for other gods, don’t go chasing after objects of your own design to try to secure your future. Don’t insist on working seven days a week because you think that if you don’t do it, the work won’t get done. Don’t steal from each other or take advantage of one another because you think the only way to get ahead is at someone else’s expense. Trust me. Trust that I will take care of you, that I will provide everything you need. Trust that I will give your lives meaning and purpose.

Of course, we know from the Bible that the Israelites struggled to heed that invitation to trust God. They wandered in the wilderness in part because they did not believe that the God who liberated them from Egypt could be relied on to be there in the future. That was the source of their sin—not some devil whispering in their ears.

Trust was also what Jesus struggled with in the wilderness. The story of Jesus’ temptation in the wilderness is purposely told in Matthew’s Gospel in a way that’s meant to remind us of the story of the Israelites in Exodus. Like the Israelites, Jesus spent some time stranded in the wilderness, and it threatened to do a number on his faith in God. He heard voices in his head that said, “Demand that God confirm that he is with you. Demand a sign that God is still present. Or better yet, just go a different direction and better your odds!”

Of course we know that Jesus weathered his crisis of faith more successfully than the Israelites coming out of Egypt. His faith did not waver. He trusted God, even to the cross. As much as anything, I think that’s what we mean when we say Jesus was in every way like us, except without sin. He trusted God completely.

Bad things happen in the world not because a devil is whispering in our ears or moving principalities and powers in the supernatural background. Bad things happen in the world, one way or another, because human beings take it upon themselves to try to secure their futures instead of relying on the goodness of God. We work too much, to the detriment of our health or family life, because we do not trust that God will provide. We chase fads and wealth and celebrities, convinced that this latest “thing” will provide the meaning we crave, when that meaning is really found in the loving purposes of God. We lash out at people different than us because we feel unmoored in a world of so much change, and we are desperate for an anchor to tell us what is true and real and reliable—when that anchor is God alone. We latch our hopes for the future on hucksters and charlatans because we feel that the world is passing us by, and we need someone to protect what is familiar, what seemed like it was ours.

The failure to trust God and God’s purposes creates in us an anxiety so desperate that we must fill that void with something else, so we go grasping for idols to make us feel safe in the wildernesses of our lives. But that grasping only leads to more separation from God. That’s what St. Augustine said sin ultimately is—our absence from God. Sin isn’t some little devil sitting on my shoulder. Sin is separation from God. Lack of trust in God leads to anxiety, and anxiety leads us to wander around in the wilderness looking for some other source of meaning, defining our life’s meaning in how hard we work, how much we have, or who we despise. And the longer we wander off chasing these idols, the farther we separate ourselves from God. That’s the source of sin in the world.

But I see good news here. If sin and evil in the world were the work of a supernatural devil, we’d have little reason for hope until we die and go to heaven, or until Satan is vanquished by God in the last days. (Indeed, that is what some varieties of fundamentalism say Christians should hope for—Armageddon, when evil will be vanquished—and in the meantime, tuck your heads between your knees and wait for Jesus.) But if it turns out that the only devils in this world are the ones we know, ourselves, then we have more alternatives for a response to sin than spiritual escapism.

I’ll take the devil I know over a devil I don’t. I don’t find the idea of an evil imp pulling strings behind the scenes in some cosmic battle with God reassuring at all. But when I remember that the devils in this world include the one I see in the mirror, I realize that the antidote to sin and evil is also that accessible. It starts with me; it starts with us. The cosmic battle for good is waged in every human heart, and we make progress against the reign of sin when we put in the work—to trust God more intentionally, to eliminate the idols and distractions and differences that separate us from God, and to look more intently for God’s presence with us in the world, including in the other people who share this world with us. Amen.

You must be logged in to post a comment.